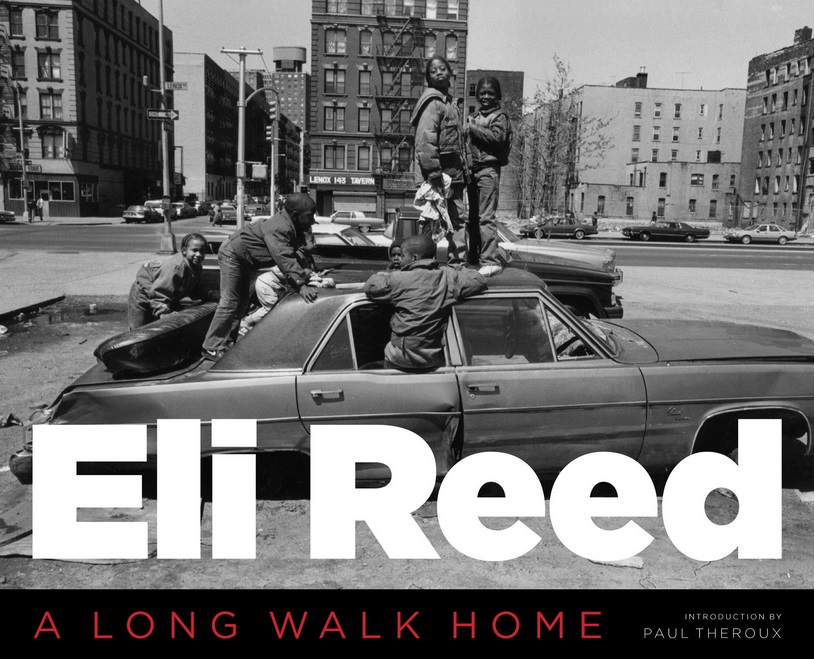

Eli Reed has been a Magnum photographer for more than 30-years, and in his first career retrospective more than 250 images are featured. The pictures included in “A Long Walk Home” feature examples of his early work, a broad selection of images of people from New York to California that serves to display a collective portrait of the social, cultural, and economic experiences of Americans in our time.

From all over the globe come pictures about life and conflict in Africa, the Middle East, Haiti, Central America, England, Spain, South America, and China. Photographs of Hollywood celebrities, women, and self-portraits have been selected to round out a monograph that enables us to better understand the human condition and the life of a gracious man, who credits many for his success as a photographer from his mother and father, to mentors to a variety of his peers, including Eve Arnold, Gordon Parks, Cornell Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Martine Franck, and W. Eugene Smith.

In his Dedication he cites Nelson Mandela and Maya Angelou as “final touchstones” for taking on the “difficult as a necessity of life and as a secure source of revelation regarding the price of living. They set the proverbial bar for courage, kindness, forgiveness, and the understanding of what one must do in order to truly live as a human being.”

He accidentally stumbled into his first full-time photography job while an ER orderly in a New York City hospital. From that inconspicuous beginning, a career was built that helped this giant of a man produce work that makes us wonder about life in general and of how difficult it must have been, and continues to be, for a black man in the world. In the Preface, he writes of being on assignment in Africa with Paul Theroux, who penned the Introduction, and talking about family.

He accidentally stumbled into his first full-time photography job while an ER orderly in a New York City hospital. From that inconspicuous beginning, a career was built that helped this giant of a man produce work that makes us wonder about life in general and of how difficult it must have been, and continues to be, for a black man in the world. In the Preface, he writes of being on assignment in Africa with Paul Theroux, who penned the Introduction, and talking about family.

“Do you realize,” Theroux said. “That your father, who was born in the year 1900, was too young for World War I, too old for World War II, and yet went through some of the toughest times a black man could go through in the United States at that time?”

It won’t take you long to see what Theroux meant, even though it was spoken years ago. The first image in the book is a portrait taken in 1998 of a man (Reed) with his head in hand, in a contemplative manner. What does he see? What is he thinking?

Where is he going? Where has he been? Although few questions are answered in this book many are asked of him and of us. From his earliest work in housing projects to his political unrest photographs he captures moments of calm amidst the storm and pressure bubbling to a boiling point.

It was a challenge for me to figure out how to review this book. What I finally decided was that I needed to page through it, page by compelling page. In order to write about it I needed to view his life as if he was living it; as if I (in a very far stretch of the imagination) were walking in his shoes.

As I walked among other people during his opening at the Leica Gallery, I couldn’t seem to focus on the photographs on the wall. There were too many interruptions, too many people, too many images to view and understand. I could appreciate the work from afar, but knew I needed to spend time with the book to better afford even the smallest hint of understanding.

A few days ago I spent almost an hour turning one page after the other, slowly and deliberately. This was what I needed to do, and what any reader should do when viewing Reed’s work: take it slow and inhale it as far as you can into your being.

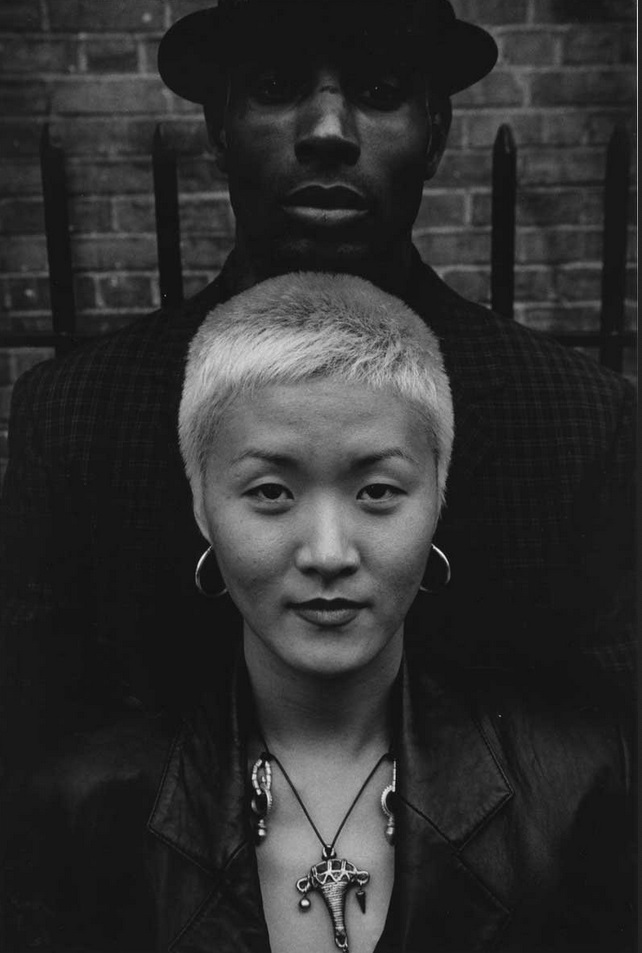

When you do this you will be in a much better position to see that it wasn’t just about the inequality of the black man that he was documenting, it was the inequality of the human race. Here is a Caucasian woman sleeping in a car, and then there is the picture of an Asian woman being held by a black man. There is no color or race separation in “A Long Walk Home.”

We come to realize after turning the last page that it isn’t just about them, it’s about all of us. We all need help. We all need understanding. Perhaps it is best to take it in sips rather than gulping life down as if it were a cold beer.

“There are no stereotypes here for the romantic voyeur; Eli’s portraits are of individuals, whose lives are evident in their faces and the paraphernalia that surrounds them,” Theroux writes in the Introduction. “Eli is a master of depicting the inner life of a person or a culture… because in his photographs, as in the greatest photographs, the surfaces—of faces and postures and gestures—reveal inner states.”

Eli Reed shows us who we have been and who we are, with the hope that who we will be will be much better.

A Long Walk Home by Eli Reed>>>

Views: 1870