For a recent project in collaboration with the Department of History of Art and Architecture at UC Santa Barbara, Mona Kuhn gained access to Austrian architect Rudolph Schindler’s (1887-1953) private archives which housed significant material, including drawings, blueprints, envelopes, letters, and a mysterious missive. With those documents in hand and the missive on her mind, so begins Kuhn’s imaginary trip through Shindler’s home and perhaps in his dreams.

For a recent project in collaboration with the Department of History of Art and Architecture at UC Santa Barbara, Mona Kuhn gained access to Austrian architect Rudolph Schindler’s (1887-1953) private archives which housed significant material, including drawings, blueprints, envelopes, letters, and a mysterious missive. With those documents in hand and the missive on her mind, so begins Kuhn’s imaginary trip through Shindler’s home and perhaps in his dreams.

Along with her at this visit is the imagined muse of Schindler, who comes to us in an unsigned letter from him to an unknown and unseen admirer, perhaps an unrequited lover.

We are introduced to her, in part, within the first few pages by a print of the exact letter: “Your dreams never, like so many, meet reality…. It is a mistake to place one’s whole world unto one point or person… the world is endlessly big… and life rich without bottom…”

With these carefully selected words, read by Kuhn, thus begins the photographer’s own experience with Rudolph Schindler and his self-designed house which was conceived as a “cooperative dwelling.”

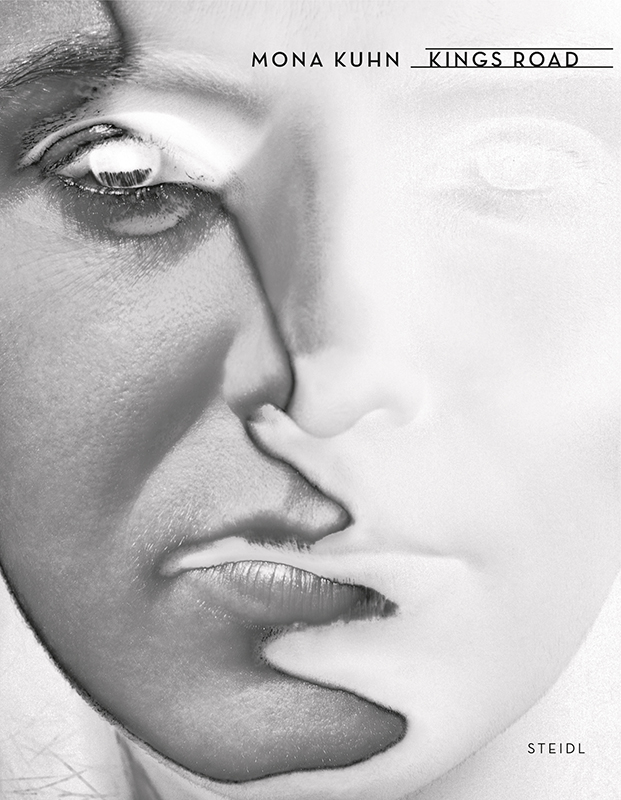

Within the covers of Kings Road are selected captures of the house itself and illustrated throughout are solarized images of the ghostly representation of the enigmatic and ethereal figure found in his archives.

In Kuhn’s process she successfully marries the present with the past with her ghostly figure wandering in and out of the house, while capturing our attention and possibly asking us to join her, as we might. She wants us to join her in her discovery of a house to which she was never invited.

My usual process in reviewing books it to first go through the entire book in an effort to see what captures my attention, immediately. Too many times I had to insert page markers for reference. Each time I paged through the book I was drawn deeper into the “story.” As one might guess Kuhn’s photography of the iconic house could be its own publication. With the addition of the figure, we are drawn even more into the history of the house and its occupant(s). It is a complementary inclusion we welcome, however, because the erstwhile muse or unrequited lover has invited us to join her in her exploration.

The imagination has been captured.

“It’s not surprising, then, that Kuhn’s photographs look like dreams. In this equivocal space, the mind has lost its geometrical homeland, and the spirit is drifting,” writes David Dorenbaum in an essay in the book. “To accept her images we must come to terms with the fact that the exaggerated nature of an image does not mean that it has been artificially produced, for the imagination is the most natural of our capabilities. Paradoxical as this may seem, our imagination is what most often gives real meaning to expressions concerning the visible world. We have to imagine very actively, in fact, decomposing the images generated by our perception, in order to allow the absent image to emerge and experience new space. By aligning her gaze with her imagination, Mona Kuhn has photographed Schindler’s house from the point of view of its ghosts. She has let a spirit speak.”

So much can be drawn from essayist Silvia Perea’s additional essay in which she describes Kuhn’s intentions as photographic fiction. She writes deftly about the woman, a supposed lover.

“Moved by the emotional crudeness of Schindler’s letter, while resisting the idea of a broken affair, Kuhn brings into the scene a lady of Pre-Raphaelite air, enacting Schindler’s lover, and captures her as she sidles through the dwelling, possibly in search of the architect or a sign that confirms their past complicity. The house the woman finds is empty, shrouded in a shadowy quietness disturbed only by the imprint of light beams and textured reflections on its bare surfaces,” Perea writes. “In stark contrast with the vibrant garden outside, a sense of impassiveness infills the dwelling’s interior suggesting its solitary aging. As the young lady moves through the space, she seems at ease, as if she was home. She hovers, rests, undresses, and lies down, possibly longing for the presence the vacant home inspires in her. All the while, the lingering light embraces her soft contours and dissolves them, figuratively fusing her body with the house’s.”

We see light and shadow (chiaroscuro) are entering and escaping the house on each and every page, just as Schindler envisioned it when he first undertook its creation. Kuhn’s images continue with this idea but enhance it even more by adding a sense of spectral participation, a Dorenbaum writes.

“Ghosts cannot exist without a void, which stands for the raw material of possible being. In Schindler’s house, ghosts enhance this void, organizing themselves throughout the locale. As we can see in Kuhn’s images, however, they also become disorganized under the very effect of the specter, locating themselves at the limit that divides interiority from exteriority, at the threshold of the visible world, in the gap between what is present and what is not,” he writes. “Blurring the boundaries between in and out, they upset the relationship of container to its contents. Persuaded by the ghosts’ presence, we see things that are not there. In their plurality, these mysterious presences induce the space to perform not only as a scene for reverie but also as a theater of alienation and uncertainty. The more our gaze wanders through the images of Schindler’s house in the company of its ghosts, the more we awaken our own.”

As I close the covers of Kings Road, it is with a bit of sadness. I have spent hours turning its pages, seeing if I missed anything. I know I will return to it, but not for about a week. I need time. I hope you will spend a good deal of time with it as well, because it is a keeper!

Kudos to Mona Kuhn for continuing to regale us with her imagination and her insatiable creativity.

• Kings Road by Mona Kuhn • ISBN 978-3-95829-755-5 • Printed in Germany by Steidl • www.steidl.de